ProSilva:

quality management in our forests

Frank

Strie, Schwabenforest PL; 14

Brady's Lookout Rd, Rosevears, 7277

Daniel

Sprod, DPIF; PO Box 46 Kings

Meadows, 7249

Duncan

Mills; Leverington, Epping Forest,

7211

Mark

Leech, Private Forestry; PO

Box 46 Kings Meadows, 7249

Abstract

ProSilva is a name given to a form of forestry management based on subtle intervention into natural processes. Similar approaches are emerging around the world because of their capacity to accommodate immediate and long term market objectives in addition to long term ecological sustainability. The fundamental principles necessary to achieve this, and the outcomes arising from it, are discussed in detail. Consideration is given to the potential for its use in Australia, in particular the advantages that the Australian context offers. Suggestions are made for immediate introduction to private forestry practice in Australia.

Introduction

Vision

A forest that offers a finely

tuned, proven and stable environment for growing trees, with simple

low impact techniques....

A forest that can be managed

for market and ecological objects, with minimal risk, to produce a range

of services to the ecology and products, occupations and experiences

for the market....

To many this will sound like a romantic dream, and yet there is a practically based, emerging philosophy of forest management that can do just that. It is called "natural" forestry or ecoforestry and is being promoted by a European centered international network calling itself "ProSilva". It has the potential to bridge the gap between outright preservation of our native forests and potential destruction.

The challenge is for us to turn this into a communicable and workable vision.

Philosophy

Science is showing much more there is to know and the magnitude of mistakes in our management of our natural world (refer ozone depletion, Greenhouse effect). Given that management has been effected largely by well meaning people over the years, the possibility is that the very foundations of our management may be fatally flawed [1] . Evidence is accumulating that reductionist science can help us identify the problems - but given the complexity and dynamics - it may never solve them in time.

This is leading to talk of a "paradigm shift' - not only in forestry - but in broader society and in the way we conduct science.

The prevailing paradigm has been a power postured, techno /economic worldview encouraging the view that complex systems could be understood by knowing enough about their parts, and pasting this knowledge together. As the inadequacies in this view have surfaced, a systemic, holistic and ecological view has been sought.

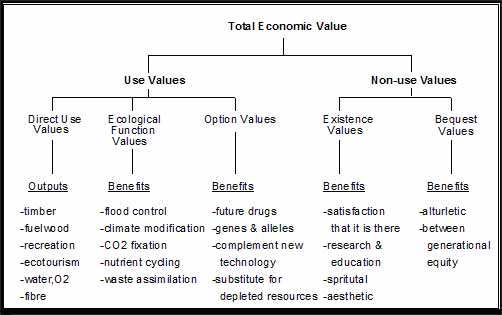

This fundamentally different view - holism - looks outwards from the problem to bodies of knowledge, and weaves strands from disparate disciplines into a single cloth, instead of looking inward at a problem from the vantage point of professional specialisation [2] . In creating this awareness, deficiencies in language and conceptualisation appear. But so too does an interlinked understanding that almost automatically integrates such previously contrasting disciplines as economics and ecology (see Figure 1).

"ProSilva " or " for the forest" , provides a cogent easily communicated name to a philosophic approach to forest management that has the potential to bridge the gap between outright preservation of native private forests and potential destruction.

It differs from accepted forestry practice in raising the emphasis of cautionary principles, long term and holistic valuation and a decreased emphasis on short-term profit maximisation, which by its very nature, is short sighted.

It differs from the hard line conservation view of ecology, in the acceptance that science, trading and the market place are an integral part of humankind's social system, and this is in turn a part of the broader ecosystem.

To develop community empathy with bush values.

To encourage a more ecologically sympathetic land use.

To provide as many fulfilling occupations as economically practical in perpetuity.

To ensure all economic evaluations satisfy ecological considerations and precautions.

To encourage the development of holistic intellectual skills and understandings of the dimensions of quality in human lives, at all levels of the human development process (Education)

Table 1: A ProSilva social development strategy

Inherent in the philosophy of ProSilva is the recognition that it fits within a new social development strategy (Table 1 [3] ).

Roots of ProSilva

Following the 1990 windstorms that devastated European forests, windthrow scattered 115 millions cubic metres of timber onto the ground and into the market4.

Forests managed under ProSilva principles by private owners were considerably less damaged, and this promoted public and professional debate as to the validity of the current management in publicly owned forest.

As a result, all German, Austrian, and Swiss public forest Authorities reviewed their methodologies and are in the process of implementing changes to management under ProSilva principles. These principles are those that have been employed by many forest cultures through-out history and around the world [4] .

Toward the end of the eighteenth century, timber became scarce in Germany: it had been exported, used as fuel for the budding metal and chemical industry and in ship building. Further, farmers had scoured the forest floors for litter to bed domestic animals, and nobility over-stocked forests with deer, who grazed any regrowth. In recognition of the continuing need for wood products, the world's first forest academy was in operation by 1811 in Tharand, Saxony, promoting monocultural cropping of trees to feed growing industrial needs.

Karl Gayer challenged this view in The Mixed Forest (1886), but it was not until Alfred Möller's The Natural Forest Concept (1922) demonstrated the efficacy of the "Plenter" system that private forest owners began to pay attention. The "Plenter" system involves managing on a single stem basis, and was developed by Swiss, Austrian and Bavarian alpine farmers because of their need for a continuous steady flow of forest and ecological products.

These ideas have progressively been implemented by private forest owners through central Europe.

In September 1950, forest professionals and land owners from south-west Germany formed "Nature-Based Forest Management" (Arbeitsgemeinschaft Naturgemaesse Waldwirtschaft), and in September 1989, professionals from 10 European countries founded ProSilva.

This organisation has since spread to Canada and Chile.

Forest Management Principles

Principle 1: Recognition of ecosystem potential

As the basis for production is the soil, attention is given to ensure the fertility is maintained or enhanced. Thus massive soil disturbance, land slip, erosion and leaching must all be avoided. This precludes such operations as large-scale clear-felling, destructive skidder operation, and mitigates against compaction and harvesting in the wet with ground based systems. Fire, recognised in Australia as an integral force in forest ecology, is still rather a blunt tool, and as such needs careful consideration before use. Favoured methods are those which build organic matter, optimise standing biomass and diversity, encourage regeneration, permit successional forces to proceed and maximise energy flow.

Principle 2: Suiting species and structures to the site

Each site offers unique potential for species diversity, tree form and timber quality. Where one site will produce tall Eucalyptus veneer and Eucryphia honey, another will produce highly figured Casuarina for cabinet-work and slow-grown Eucalyptus for fuelwood. Recognition of these potentials in Australia is made easier by pre-existing ecosystems that are still largely intact. Much discussion has focussed on local provenances, but ProSilva encourages suiting species to the site, no matter where they come from. While first choices will normally be local provenance, "superior" varieties, species from other places within Australia, and exotic spp may be used for particular purposes, taking into account ecological impacts.

Principle 3: Sustainability

Inherent in natural ecosystems are the properties of resilience (eg drought, fire), capability for self-correcting succession (under eg climate change), biodiversity (for genetic information and market diversity) and complexity (eg variety of niche and ecological structures, feedback loops). When forest managers intervene in natural ecosystems, it is essential that these properties be maximised to preserve sustainability

Principle 4: Single stem cultivation and utilisation

This is possibly the single most important management precept in ProSilva. Each tree is considered individually for future potential in the context of its neighbours. Stems may be retained for sawlog potential, "nurse" effects, seed potential, genetic value, physical location, visual and aesthetic effect, habitat value or biodiversity value. Growing, extraction, selection thinning and regeneration all occur simultaneously within the same patch of forest. Emphasis is placed on extraction of fewer, larger trees of higher value (the "plenter principle"). A forest maintaining a self-pruning, mixed age stand, with a stable microclimate will yield a continuous flow of products, services, occupations and experiences.

Principle 5: Permanent laneways

Extraction and maintenance "laneways" are established as permanent access through the forest. These minimise damage to growing stock and soil, and concentrate disturbance to minimal areas. They aid forest workers in selection of trees, in choosing the direction in which they are to be felled and in inventory management.

Actual spacing relies on site-specific factors such as species mix, age at extraction, equipment available and product quality and may vary in practice from 20 to 100 metres. Width is the minimum necessary for the extraction system.

System Management Principles

Principle 6: TQM

Total Quality Management is a set of concepts that has revitalised many industries, particularly the service and customer-orientated producing industries. The central idea is of workers throughout the chain of production focussing on their contribution toward the final customer satisfaction. In the very long-term context of forestry, this means that the forest worker must understand the consequences of thinning, felling, roading, etc; impacting on the final wood products - products that may take more than a human generation to produce.

Inherent in such a system as ProSilva is the potential for a stable career path and real self esteem for all forest workers through the valuable services given to industry and to the community. Working in stable and harmonious ecosystems are further rewards in themselves.

Principle 7: Persistent and intensive management

Methodologies employed are biologically pro-active and cost effective. Where the prevailing paradigm sees massive disturbance in a long time frame, ProSilva uses the continuing basic processes of nature, enhanced by gentle and persistent intervention to procure desired outcomes - quite a different scale of disturbance. This implies thorough planning, training and understanding the processes at work.

Equipment needs to be designed to

be ergonomic, precise, flexible and appropriate for low environmental

impact in the arenas of soil impact, pollution potential and energy

use.

Principle 8: Value of market products

Higher management costs accrued through intensity of labour and the low rate of infrastructure cost recovery require higher value in the products. Thus the focus is on producing premium quality - not only in the range of species' raw logs, but in the milling and processing. Marketing must yield premium prices. Thus the substance of Ecologically Sustainable Development and "clean, green" must be reflected in adequate pricing.

All market products are valued, including genetic information, recreation, education, research and ecotourism, clean water and unused waste assimilation capacity.

Principle 9: Landscape recovery & reintegration

Emphasis is given to designing forest infrastructure around catchment units, minimising access points, boundaries and ecological and aesthetic impacts. Thus roading hugs land capability boundaries and ridges, avoids straight lines, runoff concentration and minimises cut and fill. Visual management systems are used, with the advanced application of topographical and geographic information systems for design.

Landscape arteries such as river systems are protected, not by total preservation , but by sensitive use of appropriate machinery and management.

Corridors enabling genetic flow and

animal migration are retained, or in some instances, reinstated. This, especially in forest fringes, may entail

changed land use. Certainly there

are many instances where marginal, high rainfall agricultural country

would be reinstated to more productive forest use.

[5]

Worldwide trends

Generic terms are appearing in the literature describing a shift in forest management from a wood fibre commodity driven base to a sustainable systems base providing diverse products. New Forestry has been the main term used in the US to describe this shift. Other samples of the new jargon from around the world are ecologically sustainable forest management, sustainable integrated multiple use, total canopy, and ProSilva. It appears that although the terms are used in different ways to mean different things, there exist many similarities in the management approaches. Certainly the philosophic basis for the apparent move for change is the same - an inherent need to provide society with the greatest sustainable net worth from forests.

Many changes are implied, which become inherent as a resource which society relies on, diminishes. The need to improve utilisation at all levels is paramount as it decreases the area based pressure and improves the 'total product'. Research has revealed that the complexity of linkages in natural forest ecosystems are much more complex than foresters or scientists believed them to be. New approaches add knowledge and techniques to existing approaches, thereby generating more management options. [6]

The future will see an increasing understanding of how it is possible to achieve a variety of social goals on the same lands without sacrificing the quality of anyone. The forestry profession has an ethical responsibility to promote continuous improvement in forest science, policy and practice: but this cannot be achieved without risk. [7] , [8] James R. Lyons, America's Assistant Secretary of agriculture for natural resources and environment, with primary responsibility for the USDA Forest Service and Soil Conservation Service sums it up:

I think you are going to see a renaissance of forestry, that is, foresters developing site-specific prescriptions for how to manage public and private forestlands using all the silvicultural tools that they were taught. [9]

Relevance to Australian conditions

Despite some quite profound differences, such as a fire-adapted ecology, based heavily on evergreen Myrtacae, these ideas emanating from other parts of the world find fertile ground in which to grow in Australia.

Management of native forests in Australia has followed the classical path of exploitation, control and active management. As society now demands more than a commodity base from its forest, and given the majority of the Australian population live in near proximity to the major native forests, expectations and pressure on this finite resource is ever increasing. The successful (integrated multiple use/ ecologically sustainable) .management of these forests is now a task of great importance to the profession and practice of forestry.

Since the Routley's wrote The Fight for the Forests in 1973 [10] and were seen as traitors to the profession of forestry, the debate has broadened, the community has become more aware and research has shown the lack of understanding of the long term impacts of forest use. There have been many changes to the once autocratic forest services and a plethora of conflicts, public enquires and decision making processes relating to forest land use have been undertaken. As the US Forest Service embarked on its New Perspectives program, Tasmania was struggling with its Forest & Forest Industry Strategy, a consultative landuse decision making process.

The Resource Assessment Commission has identified three major issues following its exhaustive assessment of the national situation:

1. that there is no justification for ceasing wood production in native forest,

2. there is uncertainty regarding long term impacts and a need to integrate resource management & conservation and

3. a lack of research into impacts of forest use on ecological process. [11] .

The adoption of new site specific silvicultural practices in the management of Australia's forests will take place. There is a need to base the management of the future on high scientific objectivity. However, it is observed that some of the proposed applications or proposed practices can be viewed as working hypotheses or experiments until they are verified.

The importance of biological legacies discussed in the recent literature is of fundamental importance in the Australian biota where fire, particularly in the forests of the south-east, has provided repeated catastrophic events. The debate in adopting any non-fire/low fire management options, is intensified when fuel load management is introduced following a devastating fire event. This must be given a high priority in evolving systems of ecologically based sustainable forest management. Historically the various forest ecosystems in Australia have a broad spectrum of natural fire frequency, intensity and patchiness. However, 200 years of use of the forests has created a different environment with a changed set of values. The inappropriate use of alternative silvicultural methods may result in a long term loss of sustainability if a higher risk of a catastrophic fire event is not included in the equation. The use of appropriate systems, including fire, to strategically address the maintenance of asset values given by society must form part of any new and sustainable management system.

There is much collaborative multidisciplinary research being undertaken in Australia to balance ecosystem conservation and sustained wood production. Much of the effort has been based on allocation or separation of use to achieve the balance. The way of the future sustainable systems will be an increasing move towards truly integrated multiple use, to produce the greatest net benefit on any given site.

The debate in the US and Europe of the need for and rate of change is very intense within and without the forestry profession. Australia has rapidly embraced new appropriate technologies and leads the world in many areas. Let us as a nation be leaders and not be in a position where we are caught by a shift in consumer demand. If the concept of forest product certification based on a number of sustainable criteria is introduced more comprehensively by the major trading nations the issue of ecologically sustainable forest management will be forced on us or become a major barrier to trade.

Australia is well placed to facilitate new, more site specific practices. As the world demand for quality hardwoods increases, the expected increase in their value should allow more intensive site specific silvicultural systems, which are currently not feasible to be applied in the future

We have some unique advantages:

We still have some sound forest ecosystems that retain their biodiversity and structure, and provide us with working ecosystem models. Central Europe never had this biodiversity due to early Holocene ice sheet scouring, the barriers to colonisation presented by the Alps, and the subsequent ecosystem simplification wrought by human activity [12] .

Even in synthetic and degraded ecosystems such as those now occupied by agriculture and plantations, we still have sufficient genetic material, information and modelling techniques to construct an approximate structure of the original proven forest ecosystem.

We are perhaps more open to change and adaptation than older cultures as attested to speed of adoption of technology (eg VCR's, microwave cooking and second highest PC ownership in the world). Our sense of community and compassion for the weak or disadvantaged is also strong - a sensitivity that is vital in caring also for the forest community.

Two perceptions of central European, or northern hemisphere forests must be addressed:

1. These forests are not only softwoods. High quality deciduous hardwood such as oaks, beech, maple and ash are just as important.

2. Equally, different species in the northern hemisphere display the full range of shade intolerance as do our species. For instance, in our forests, myrtles and blackwoods lie at one end of the range, Eucalyptus delegatensis and E. obliqua around the middle, and E. regnans and E. nitens at the other.

Relevance to private forests

ProSilva is especially suited to implementation in private forests. Diversity of ownership spawns diversity in forest management objectives, and thus provides a rich ground for the uptake of "experimental" ideas.

Private owners benefit from a timely flow of products and services from their property: the ability to harvest one log to meet a payment on a machine, or several to satisfy the tax-man particularly suit them.

They furthermore have a deep commitment to long term future of own property. Most farmers consider the future generations in their actions, as they have often seen the impact of previous generations on their own profitability, and will be likely to forego a quantum of present profit for their children's future's sake.

Benefits and Challenges of ProSilva

Benefits

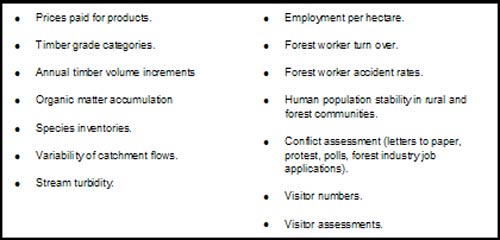

Benefits fall into three major categories: economic, thorough production of premium quality, diversified products; sociological, thorough provision of fulfilling, sustainable, well-placed jobs; and ecological, through enhanced landscape stability. Some variables to measure progress toward these goals are listed in Table 2.

1. Economic: Given a forest production cycle of 30 -60 years , who is able to predict market demand? Diversity based on the balance of natural communities, providing in general terms a low cost, low risk strategy.

Failures in regeneration compound reductions in mean annual volume production due to short rotations - estimated in some instances to be only 60 - 80% of that possible under longer rotations. [13]

2. Marketing quality timber: As basic human needs of shelter and materials are satisfied, the aesthetic values of forest and timber become the focus of more sophisticated human demands. Extrapolating current economic growth, the demand for aesthetic based forest products is destined to grow. Already in Europe , the market has paid over $20,000/m3 for select veneer quality timber, with the median price for standard oak being $400M/m3 . [14]

3. Sociological: Complex, diverse production systems are very people intensive (both labour and intellect), requiring care, skill and understanding. From the careful considered felling of each individual stem, to the thinning and culling of regrowth and activities like fire prevention, such intensity offers a multitude of fulfilling occupations. This helps meet the need for jobs created by productivity growth and job shedding in the manufacturing and service industries, and furthermore provides jobs in depressed rural settings.

4. Catchment quality: Minimal disturbance, limb and leaf drop mulching and maximisation of leaf area are associated with diversity and successional processes, and favourably affect catchment quality. Encouragement of fast growing pioneer species such as the Acacias to shade grasses and create surface mulches provide non chemical means of weed control, as well as timber and ecological benefits.

5. Landscape, biodiversity and aesthetic quality; The principles of ProSilva allow for a higher value to be assigned to these historically undervalued benefits, whilst still allowing extraction. Areas which are managed in this way will complement areas retained for their true wilderness quality. Some of these benefits overflow into ecological services for agriculture such as nectar sources for parasitic flies and wasps, habitat for insect eating birds and animals, and climate modification.

Challenges

1. Greater demand for skills: Compared to the current simplistic culture of

extractive use, the concept of quality management must be developed

amongst the forest managers and operators. Smaller management and ownership

units found in private forestry lend themselves to this type of management.

In Europe, there is an average of one professional field forester to 6000 hectares compared with one to 100,000 hectares in Tasmania [15] .

2. Slower infrastructure cost recovery: Infrastructure costs must be recovered over a longer time frame. Capital costs cannot be subsidised by exploitation of "natural gifts".

3. Complexity of marketing system: Management of production forests for multiple species and multiple products varies from one plant community to another, requiring a much more sophisticated and coordinated processing and marketing system.

4. Supervision costs: People intensive businesses as distinct from capital intensive industries are inherently riskier and difficult to run successfully, particularly in a dispersed workplace such as a forest. Consequently ecoforestry requires a more sophisticated, self motivated, professional culture by all workers. However, ethical goals and quality associations offered by ecoforestry inherently make it easier to attract and keep forest staff of high calibre, potentially offsetting problems of a more people intensive industry.

5. Training costs: Developing the levels of skills and understanding required by the forest workers will be substantial. However once a "New Silviculture", is established, much can then be passed on through on-the-job experiential means and by traditional apprenticeship.

Developing a ProSilva strategy

Action plans

Forestry is at a cusp. Movements from around the world are starting to point in a similar direction - a direction that integrates multiple use of our conditionally renewable forest resources and recognises human and non-human requirements and values. We have the opportunity to develop networks for rapid sharing of hard-nosed, practical experience, but these will not happen of their own accord. Thus is proposed that an organisation be started to achieve these ends.

Table 3 enumerates actions that can empower individuals in management of their own private forests.

A fresh organisation may have the ability to weld together previously disparate groups into a cohesive whole, setting up trust and linkages, where now there is conflict.

Certainly one of the most important actions to take is developing good educational links. This can occur through existing forums such as field days organised by forest consultants or Private Forestry Corporations, but more probable is involvement in a ProSilva network.

Other forums may be provided through

Whole Farm Planning for practicing land managers, or University for

potential professionals.

1. Establishment and maintenance of an ecoforestry network.

2. Location and listing of demonstration forests

3. Forest manager orientation courses and field days.

4. Preparation of ProSilva forest practices code.

5. Forest operator training courses.

6. Certification of forest managers.

7. Forest product endorsement and labelling scheme.

8. Public education program.

9. Forest practice awards.

10. Public policy briefings.

Table 3: Potential actions for developing ProSilva

Implications for forestry and land management

"ProSilva" is both the nametag and a possible vehicle for the practical extension of the worldwide paradigm shift that is taking place in natural resource management. For our forests it offers the hope of peace and fulfilment for our community., There are many values that the market process cannot guarantee, so practical community shared philosophy and ethics must be the framework for the management of our forests.

This paradigm shift is reflected by the ProSilva philosophy, requires a fundamental ethical shift from every individual, from power towards care oriented roles. It is possible that it is the ultimate test of humankind, a test that must be passed, if future generations are to be assured a life of quality and dignity.

[1] Bawden, R.J., Systems Thinking and Practice in Agriculture, USA J. Dairy Sci. 7(7), 1991

[2] Savoury, A., Holistic Resource Management, Island Press (1989)

[3] Young, M.D., Sustainable Investment and Resource Use UNESCO/Parthenon 1992

[4] Der Dauerwald #8, June 1993, #9 December 1993

[5] Sauders, D Reintegration of Fragmented Landscapes

[6] Franklin, J.F : Scientific basis for New Perspectives in forests and streams. in Watershed management; Balancing Sustainability and Environmental Change.1992

[7] Clark, R.N. 1990 : The emerging web of integrated resouce management

[8] Difley, J.A. : 1993 President's Commentary American Journal of Forestry Dec 1993

[9] Lyons, J.R, in an interview with Rachael Allison: Administration Policies and Old-Growth, US J. For., Dec 1993

[10] Routley, R & V, The Fight for the Forests, 1973

[11] Squire,R.O. 1993 The professional challenge of balancing sustained wood production and ecosystem conservation in the native forests of south-eastern Australia Aust. For. 1993 56(3) 237-248.

[12] Roberts, N The Holocene, an Environmental History Basil Blackwell, Oxford, NY, 1989

[13] DeBell & Curtis, Silviculture and New Forestry in the Pacific Northwest, J. For., Dec 1993

[14] Holzmarkt im Dezember 1992, AFZ, 25 1992

[15] Anon, Forestry Comm Tas, An Rep 1992/3

© 2002 Pro Silva Ireland | Feedback | Imprint